'That scrapbook of expressionism.'

'That scrapbook of expressionism.'--Fritz Lang on Citizen Kane

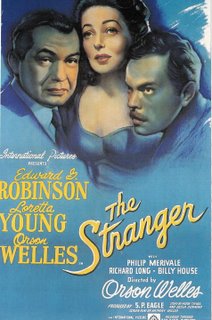

It's still hard for us to comprehend the chaos and disillusion immediately following WWII. Any number of illusions about Western civilization were shattered, and the world as they say, has never been the same since. Our present-day cynicism was unthinkable to most Americans prior to the Second World War, and something like the Holocaust was impossible to even imagine. 'The Stranger' enters-into that twilight-moment between the realizations and the resulting-cynicism of a new-age, and has an unintended-link to Welles's theme of "lost-edens", and of lost-innocence. Lost innocence is the main-theme of The Stranger, and Orson Welles does it in a larger-than-life style that marks all great cinema. There are a number of compostions that are simply expressionist: Edward G. Robinson with a web-like shadow cast on him as he draws his own prey into his own web is as powerful as some of the best German Expressionism. Welles was so good at this, he intimidated Fritz Lang, who cold-shouldered the young-director during his time in Hollywood. It's also likely that Lang was worried Welles would usurp his own anti-fascist credentials as a filmmaker. The post-war era was one of uncertainty, which always makes for good drama!

Those wonderful low-shots from 'Citizen Kane' are there, and much-much more! Welles's use of wide-angle shots comes into its own here, though it is nearly invisible as technique. The film was popular in its day, and it kept Welles in the Hollywood game a little-longer (as it was designed-to), but not at RKO. This would be his final film for the studio. It's funny that people underrate this film, and I ascribe this to baggage--and how could anyone dare say Welles's acting is 'wooden'?! He is unconvincing if you don't know the historical-background of the era. The Stranger is a very 'Langian' film in the Welles-canon, and it makes us feel complicit with a Nazi-character. For 1946, this is an impressive lesson-learned by Welles and co-writer John Huston on the subject of collective-guilt. The bulk of the screenplay was executed by Anthony Veiller, from a story by Victor Trivas, but rest-assured the anti-fascist message is all Huston and Welles. It should be noted that The Stranger is possibly the very-first commerical motion-picture to show the horrors of the Holocaust in Europe. Many Americans got their first-glimpse in this film, since the military was forbidding the dissemination of footage at this time. Perhaps this was Welles's other sin--the first being Kane-- against the establishment of 1946?

Many Americans had fought-against Nazi Germany (and industrial-employers in the labor-struggle, since many unionists equated Big Business with Fascism, and National Socialism was supported by certain industrialists like Henry Ford) to end European-fascism. There was an idea of a 'United Front' against fascism within the Old Left that had carried-over from the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). Edward G. Robinson's Nazi-hunting character (possibly the first in an American film) represents a continuation of this Old Left trend that arose during the Great Depression. Surprisingly, it even survived the war. But this inertia would be squashed by the anti-Communist backlash, and the creation of the Cold War witchhunts by people like Richard Nixon, Thomas Dies and many others in Congress and the State Department/Executive Branch. In 1946, Germany was central to EVERYTHING, and The Stranger represents a specific-moment in our culture--an incredibly-important one. Sometimes, a movie is smarter than the audience (and more mature), and yet can still be entertaining.

The exchange-between the Robinson-character and the Welles-character (Franz Kindler) on whether Karl Marx could be German because he was a Jew was echoed in most anti-Communist literature of the era. It was not simply Nazis who believed this, but radical anti-Communists like Gerald L.K. Smith and his ilk in the American Bund. It also existed in the halls of Congress in 1946. And while this film is certainly to be viewed as a stab at European and American fascism, it is really a great thriller, too. There are so many shots in this film whose composition can only be called dead-on; it is a riveting crime-drama that equals Hitchcock's work in the same period, sometimes outdoing-it. An on-the-run Nazi was VERY exciting in 1946, and for many, it wasn't so difficult to imagine. A number of reviewers have noted that Welles's dialect is 'too-good', but one should remember that there were German-Americans who returned to Germany to join National Socialism's ranks. Many of these individuals had been born in the United States, and so, a prominent-Nazi speaking perfect-English is not really far-fetched.

A 20-minute South American prologue of Kindler on-the-run was cut (and lost?) by RKO-executives, possibly due to political-pressure from the State Department, who were busy hiding 'useful' Nazis ('Good Germans') in 'Operation-Paperclip'. Welles and Huston (like Chaplin) can be seen as a members of the 'Old Left', which is a fine-distinction over being a Nazi/anti-Communist (and I hate Communists, too!). This film has everything you want from Orson Welles, from the small-town checkers games at the Pharmacy shot in intense close-ups, to the incredible clocktower finale, it's simply time for a reassessment of such a great film noir! Buy the Roan group DVD, it's got an additional 10-minutes over the standard 85-minute cut, and the quality is excellent. How often does a thriller REALLY put you so close to the killer? Underrated, a gross-sin.

No comments:

Post a Comment